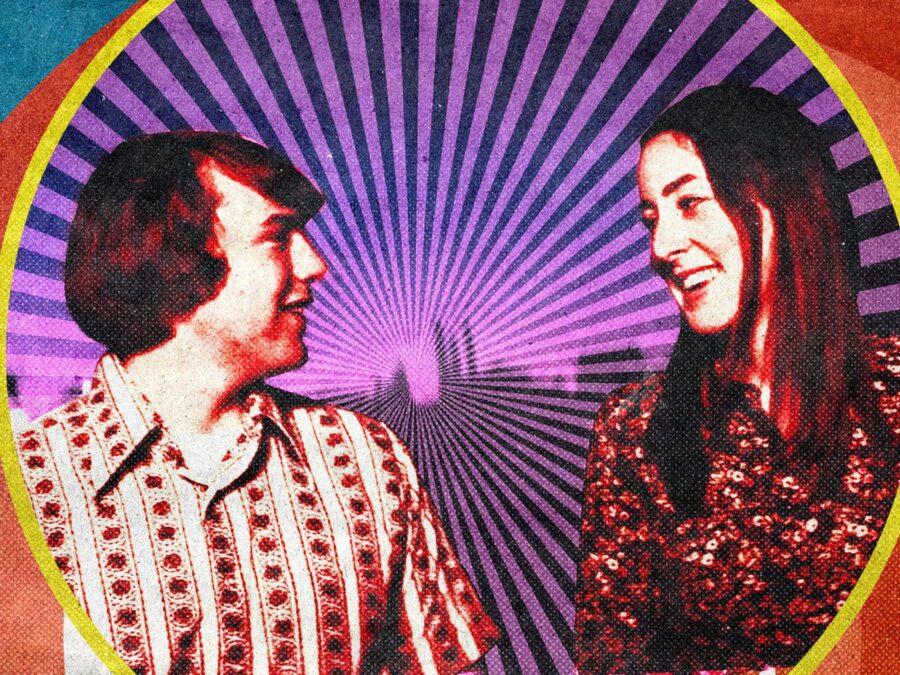

What color licorice are you having on your pizza? This one is filled full of emotion with an aggressive business model. Paul Thomas Anderson film makes you believe you can do anything…

Watching Gary Valentine played by Cooper Hoffman made me feel like a real underachiever. But it inspired me to write this review.

There is something about stepping out of the theater after watching a P.T.A. film. This one made me appreciate having emotions no matter how strong or weak.

Alana Kane played by Alana Haim gives a performance that should be recognized. The wardrobe colors immersed with the sounds of the music.

Here is the recipe for Licorice Pizza: First you have a great writer and director. Second you add a genuine cast. Polish it with beautiful score. Fill it with a gold soundtrack.

If you want to see an inspiring romantic dramedy, I recommend Licorice Pizza. My marks are below thanks for reading:

- Movie – 8.7/10

- Acting – 9.5/10

- Score – 9.7/10

- Soundtrack – 9.6/10

- Wardrobe – 9.5/10

P.S. Young Hoffman reminds me of a young Matthew Broderick and of course his father much Love Phillip.

Look for my studio review this weekend. Where I sit down with Matt and we have a conversation about the film.

-(BKB)

Check out the Licorice Pizza Trailer Below!